Case studies provide brief examples when applying classification stages for the different aspects of the development of the wheelchair sector. If actions further to the country’s situation analysis were implemented, outcomes of these are described, and all cases present a brief statement on the way forward based on the situation analysis results and actions implemented (when applicable).

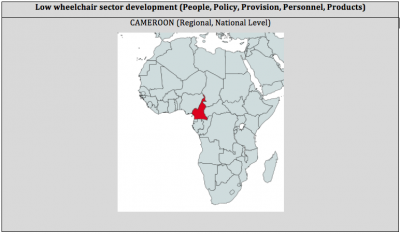

Cameroon

Legislation on the provision of AT devices in Cameroon is inferential and in its infancy. Though not explicitly stated, laws No. 83/013 of July 21, 1983, and the mandate to its implementation, No. 90/156 of November 26, 1990, refer to protecting Cameroonians with disability through empowerment and inclusion in mainstream society, for example, in education, employment, and through universal design of buildings and structures [34-36]. More recently, in parallel to signing the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2008, the President of Cameroon, Paul Biya, appealing the statutes of 1983 and 1990, invoked ordinance No. 2010/002 of April 13, 2010, focusing on the prevention of disabilities through the social development approach of national solidarity [34, 37]. National solidarity refers to an outcome driven agenda promoting “security mechanisms, compensation, promotion or valorization of socially vulnerable populations for their empowerment and the restoration of their human dignity”[37, 54]. AT could, therefore, be seen as an underlying entity deeply embedded in current national development schemes that is yet to be sanctioned.

In 2005, under the Ministry of Social Affairs, the First Forum on National Solidarity was held in Yaoundé, Cameroon [37, 54]. The forum brought together national administrations, organizations, and stakeholders with a goal of preventing exclusion of the most marginalized and vulnerable groups [37, 54]. Within the Ministry of Social Affairs is the Social Protection of Persons with Disabilities and Older Persons Department, which is responsible for implementing health related policies for PWDs and supporting disability inclusive development programs in the country [37, 54].

Although part III (section 16 to 24) of the April 2010 disability law articulates government’s commitment to support the rehabilitation of PWDs, currently, no provisions exist on wheelchair service delivery, exclusively. Service providers rely on wheelchairs procured through donations and inappropriate distribution strategies, with little to no training in how to provide them to users. Often, the wheelchairs are not adjustable, can’t be repaired locally, and are unsuitable for the rough terrain of the area. Thus, resources are wasted from clients abandoning the technology that was prescribed.

A major outcome of the forum was the creation of the National Solidarity Fund, which allocates funding resources to underserved groups, including PWDs, for health, education, and socio-economic purposes. The forum also engaged all participants to reconvene periodically with the Ministry of Social Affairs to ensure implementation of the agreed recommendations and follow-up work.

- Advocate and influence political leaders and those responsible for implementing health agendas to include and emphasize AT policy and provisions in legislature to further support disability inclusive development.

- The national solidarity approach and the development of the forum with allocated funding provide a solid foundation for disability inclusive development organizations to leverage AT propositions. Though disability services depend on wheelchair donations from non-profit organizations, as a first step, funds could be used for training and capacity building of service personnel to ensure individuals with mobility needs receive the most appropriate technology available.

- Inform high-level stakeholders on the importance of adopting wheelchair service provision standards and guidelines, while adapting recommendations for contextual appropriateness.

- Within the framework of Sustainable Development Goal 17, disability service providers should continue to explore global partnerships for the provision of appropriate AT to disenfranchised PWDs.

Romania

Romania signed the UNCRPD in 2007 and ratified it through Law no .221/2010, assuming the government’s moral and legal obligation to implement it. The Optional Protocol to the Convention was signed by Romania in 2011, but it is not yet ratified. In Romania, the National Authority for Persons with Disabilities (NAPD) was originally assigned as central coordinating authority to implement the UNCRPD. Subsequently, however, another institution under Law no. 8/2016 took on this role with the creation of the Council for monitoring the Convention’s implementation, under the Parliament control. The council’s main purpose is to monitor the exercising of rights for individuals with disabilities in residential public or private facilities, as well as hospitals and psychiatry units. The impact made by the council is not yet evident, as implementation of services is still under development, with personnel and infrastructures currently being established.

The Romanian legislation on disability assumes to a certain extent the Convention’s recommendations about the right to mobility. The social protection of persons with disabilities is regulated mainly by three important pieces of legislation:

- Law no. 448/2006 that sets out the general framework of rights and obligations of persons with disabilities, dedicated to social integration and inclusion

- Law no. 292/2011 on social assistance that defines and regulates the national welfare system

- Government Decision no.655/2016 that approves the National Strategy “A society without barriers for persons with disabilities” 2016 – 2020 and the Operational Plan for implementing the National Strategy

- A clear understanding of wheelchair service delivery in Romania is lacking, given limited statistical data and research evidence available. In order to address the needs of people who use wheelchairs, greater awareness and understanding of the issues is required.

The Motivation Romania Foundation investigated the wheelchair sector in Romania, considering level of need, funding, access to wheelchairs and wheelchair services, in-county providers, formal education and training, existing research and stakeholder perspectives. Findings generated a better understanding of the situation to assist in the production of a Strategic Plan to address disparities that exist to provide appropriate wheelchairs.

- There were no official statistics found specifically about the people with personal mobility impairments or about the people who need and/or use a wheelchair. Based on international figures, it was estimated that the percentage of people requiring a wheelchair should be around 1.5% of Romania’s population (19,820,000), or approximately 297,000 people would need a wheelchair.

- People with personal mobility impairments’ access to wheelchairs depends on the potential funding sources. The Romanian government assumes responsibility to provide a small subsidy for a wheelchair every five years. The national health scheme covers technology products (not services), including wheelchairs but excluding wheelchair services. The Ministry of Health is responsible for the provision of wheelchairs. Evidence suggests that the Romanian health system is seriously underfunded and poorly managed. Wheelchairs are provided by suppliers approved by the Ministry of Health and are contracted yearly by the County Health Insurance Authority (CHIA). Private insurance does not specifically cover the cost of a wheelchair; this is usually included within an overall lump sum compensation for invalidity.

- The process of prescribing a wheelchair does not include a comprehensive assessment, and prescription is related to product rather than individual needs. Referred by the family physician, the user goes to the specialist physician (neurologist or orthopedist) and gets a prescription for a wheelchair. The prescription includes no specific details or requirements about the wheelchair, just a general recommendation as to the need for a device. With the prescription, the person submits a request to the County Health Insurance Authority. Once approved by CHIA, the user gets a voucher and the approved list of the local contracted suppliers. Suppliers provide a wheelchair within the agreed fixed price. Wheelchair products are imported, usually low in cost and quality. Follow up and maintenance services are limited.

- Formal education and training is ad hoc, lacking in uniformity across therapy programs. Course content contains some related subjects; however, no specific wheelchair service delivery education courses exist. Motivation Romania Foundation (MRF) provides non-formal programs with specific focus on wheelchair provision.

- Limited published scientific research exists regarding wheelchair user population and service delivery.

Stakeholder meetings generated a collective perspective, revealing a number of priorities to build a sustainable wheelchair service delivery system. These priorities included increasing awareness of all, at societal, government, provider and user levels; national review of services, producing a database to established overall service needs; education and training; and accessible public environments. These situational analysis and stakeholders meeting provide the basis for Romania Strategic Plan for the wheelchair sector that aims at designing a strategy for improving the situation of wheelchair users, in order to “enable persons with disabilities to live independently and participate fully in all areas of life“[1].

- Raise awareness at a local, regional and national level as to the importance of appropriate wheelchair provision.

- Engage with the relevant Romanian government departments to present issues and solutions regarding wheelchair service delivery. Government commitment to address wheelchair service delivery in Romania is essential to developing a sustainable system.

- A national review of wheelchair services is required to develop a national database, assessment and delivery processes, education for all to raise awareness as to the importance of appropriate wheelchair provision, education and training for personnel involved.

- Work with academic institutions to develop accredited education and training programs as part of continual professional development for professionals. In addition, generate a strategy for research and development in this area.

- Strategic actions require prioritization, giving consideration to what is desirable and feasible to achieve in the short, medium and long term.

Indonesia

National health insurance in Indonesia precludes coverage of assistive aids such as wheelchairs and prosthetic & orthotic devices [19, 55]. However, since 2013, the provincial government in Yogyakarta (city in Java) has implemented a unique social health insurance scheme catering to people with disabilities within that region. The insurance scheme titled ‘Jamkesus Disabilitas – Jaminan Kesehatan Khusus Disabilitas’, provides coverage for medical care, treatment and assistive aids, which include wheelchairs. Based on several years of implementation of the scheme, stakeholders found that an area that needed to be focused on was reference standards when it came to assistive technology (AT) service provision.

The Provincial Health Office of Yogyakarta and the Jamkesus Disabilitas Administration Body conducted a workshop in February 2017 to design a framework with regards to AT products and services for the Jamkesus Disabilitas scheme. Organizations that supported the workshop were United Cerebral Palsy (UCP) Wheels for Humanity & UCP Roda Untuk Kemanusiaan, with support from USAID. International experts from the World Health Organization, International Society of Prosthetics & Orthotics, International Society of Wheelchair Professionals and International Standards Organization TC 173 provided an overview on the global standards. Approximately 60 people from UN agencies, professional associations, Disabled Peoples’ Organizations (DPOs), provincial and local organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) attended the workshop.

Based on expert recommendations and group consensus, it was agreed upon that passing the ISO 7176 standards was mandatory to ensure high-quality, safe and durable devices would be provided through the scheme.

The workshop resulted in two action items:

- Create a partnership with the Social Agency, Health Agency and NGO’s to educate users and their family about the importance of providing an appropriate wheelchair for each individual and wheelchair maintenance.

- Create a product standards committee consisting of various stakeholders.

The Jamkesus Disabilitas scheme provides an excellent case study on the adoption of standards for both products and service for AT service provision. Success of the scheme will pave the way for nationwide adoption of products and service standards, given that both private and public national stakeholders have shown keen interest in the functioning of the scheme.Way forward

- Build buy-in with the MOH to design a community based service delivery model; this includes shifting centralized responsibility for service provision from the hospital to the primary health care level and structuring related capacity building guidelines and management systems.

- Build the cost effectiveness argument for global standards ISO 7176 so governments require manufacturers and suppliers they procure from to meet these standards.

- Build buy-in with the MOH to design a community based service delivery model; this includes shifting centralized responsibility for service provision from the hospital to the primary health care level and structuring related capacity building guidelines and management systems.

- Build the cost effectiveness argument for global standards ISO 7176 so governments require manufacturers and suppliers they procure from to meet these standards.

Thailand

Since WHO guidelines on the provision of manual wheelchairs in less-resourced settings was launched in 2008, Sirindhorn National Medical Rehabilitation Institute (SNMRI)[1] started to work in partnership with Motivation Australia to improve wheelchair service provision in Thailand. The 3-year project started by building capacities of SNMRI’s staff. A 2-week training course called ‘Fit for Life’ was conducted, followed by ‘the Supportive Seating’, which is also a 2-week training course. After that, SNMRI implemented wheelchair services and developed the Guideline on the Provision of Manual Wheelchairs for Health Personnel [56]. A 3-day training course was conducted along with the guideline between 2010-2012. Around 68 health personnel from 45 community and provincial hospitals attended.

After the WSTP-Basic level was launched in 2012, a representative from SNMRI attended the WHO WSPT-B regional training in Hong Kong supported by the WHO – Western Pacific Region (WPRO). Since then, the WHO WSTP-B has been implemented in Thailand. Health personnel from hospitals were invited to attend the training, which is conducted annually. The WHO WSTP-I has been conducted since 2013 after the Global launch in Cape Town. The Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health financially supports the trainings. Around 25 participants from 10-15 different hospitals attended the trainings each year. From 2013 to 2016, around 100 health personnel from over 40 hospitals attended the WHO WSTP-B & I. Moreover, in 2015-2016, participants from Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei were invited to attend the WHO WSTP-I in Thailand, which aimed to build networks among WPRO service providers in the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) community. Thai government financially supported the training.

- Work with the ministry of health and ISWP on strategies to integrate the WHO-WSTP into rehabilitation training programs strategy

- Form a credentialing committee by consulting international bodies such as ISWP on the certification process, maintaining license and methods for continuing education.

[1] Sirindhorn National Medical Rehabilitation Institute (SNMRI), the Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health (Nonthaburi, Thailand). Services provided include medical rehabilitation programs, basic and intermediate wheelchair services in the Assistive Technology Unit (AT) where occupational therapists and physical therapists work closely with technicians in the same space. The unit is completely separated from other therapy units.